|

City information

Puerto Ayora.

With an area of 986 Km2, this is the second largest island of the Archipelago. Its highest point, Crocker Hill, goes up to 864 Mts. above sea level. Its principal city is Puerto Ayora, which is the place with the main economic activity, and also the center for tourism in Galapagos. Here functions The National Park's office, as well as the Charles Darwin Scientific Station , where you can visit the Van Straelen Exhibition Center and the incubation and raising of the Giant tortoises, where you will observe the baby tortoises before their repatriation to their natural habitat, and you will also meet Lonesome George, the only survivor of the Pinta Island subspecies. Another interesting site is Tortuga Bay, a beautiful beach surrounded by mangroves where you can observe sharks, Manta rays, marine iguanas and several sea birds. Beaches such as this one, surrounded by nature, and without the track of humans, are the example of the unrivalled beauty of Galapagos. Bachas are two adjacent white sand beaches, where people can swim and practice snorkel. In a close by lagoon, you can watch flamingos. Black Turtle Cove is a salt-water lagoon surrounded by different mangrove species and in its quiet crystal clear waters you can observe marine turtles, sharks and rays. Lava tunnels, of more than a kilometer in length, were made by the solidification of the surface of a lava flow. When the flow stops, the liquid lava inside keeps on flowing, leaving the exterior surface solidified and forming the tunnels.

Rules of the Galápagos National Park

On the island, groups of no more than 15 visitors are led by a naturalist certified by the Galápagos National Park Service. With this policy it is intended to reduce the impact on the fragile ecosystems while providing a sense of solitude and privacy on the Islands.

Don´t take anything from the islands, but photographs, and leave only your footprints.

-

Please do not disturb or remove any native plant, rock, or animal.

-

Please be careful not to transport any live material to the islands or from island to island. Each one has its unique fauna and flora and introductions can quickly destroy their balance.

-

Please do not touch or handle animals. Even the fearless animals of the Galápagos require a certain distance, and do not like to be encroached upon. Please respect this distance as attempting to touch them will disturb them.

-

Please do not feed the animals. This can be dangerous to you and it will also affect the social structure and natural behavior of the animals.

-

Please do not startle of chase any animal from its resting or nesting spot.

-

Please stay on the marked trails. Many people visit the islands and it is important that people do not damage vegetation or cause erosion.

-

Please do not leave, or throw any litter over board.

-

Please do not buy any souvenirs made from native Galápagos precuts, (except for wood) as this encourages the exploitation of these resources. Especially do not buy sea lion teeth, black coral, or tortoise / turtle shell products.

-

Do not smoke on the islands.

-

Do not hesitate to show your conservationist attitude.

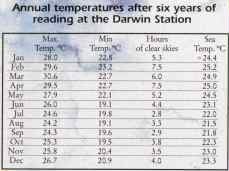

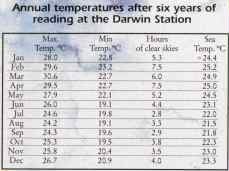

Galapagos Islands weather

click to enlarge pictures

The Galápagos Islands

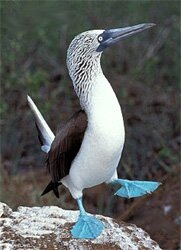

The Galápagos archipelago is famous for its fearless and unique wildlife. Here, you can swim with sea lions, float eye-to-eye with a penguin, stand next to a blue-footed booby feeding its young, watch a giant 200kg tortoise lumbering through a cactus forest, and try to avoid stepping on iguanas scurrying over the lave. The scenery is barren and volcanic and has its own haunting beauty. The Islands lie on the equator, about 1000km west of Ecuador, and consist of 13 major islands and many small ones. Five islands are inhabited. The Galápagos as a whole are one of Ecuador's 21 provinces.

The islands were discovered accidentally by Tomás de Berlanga, the Bishop of Panama, in 1535. He was on his way to Peru when his ship was swept 800km off course by the currents. In a letter to the King of Spain, the bishop was less than enthusiastic about the islands: "I do not think that there is a place where one might sow a bushel of corn, because most of it is full of very big stones and the earth there is much like dross, worthless, because it has not the power of raising a little grass". Like most of the early arrivals, Bishop Tomás and his crew arrived thirsty and disappointed at the dryness of the place. He did not even give the islands a name.

The islands first appeared on a map in 1574, as "Islands of Galápagos", which has remained in common use ever since. The individual islands, though, have had several names, both Spanish and English. The alter names come from a visit in 1680 by English buccaneers who, with the blessing of the English king, attacked Spanish ships carrying gold and relieved them of their heavy load. The pirates used the Galápagos as a hide-out, in particular a spot north of James Bay on Santiago island, still known as Buccaneers' Cove. The pirates were the first to visit many of the islands and they named them after English Kings and aristocracy, or famous captains of the day.

The Spanish also called the islands "enchanted" or "bewitched", owing to the fact that for much of the year they are surrounded by mists giving the impression that they appear and disappear as if by magic. Also, the tides and currents were so confusing that they thought the islands were floating and not real islands. The Spanish also called the islands "enchanted" or "bewitched", owing to the fact that for much of the year they are surrounded by mists giving the impression that they appear and disappear as if by magic. Also, the tides and currents were so confusing that they thought the islands were floating and not real islands.

Arrival and establishment

When the tips of the Galápagos volcanoes first appeared above the sea's surface some three to five million years ago they were devoid of life. The ancestors of every plant and animal species native o the islands must have arrived there from some other part of the world. We will never know exactly how colonization occurred, as such events do not leave records for us, but we may guess about what probably happened. A thousand kilometers of ocean separate the Galápagos from the mainland. Despite this barrier, a large number of species have made it to the islands. Oceanic volcanic islands such as the Galápagos differ from continental islands in that they never had contact with continental land masses. Any plant or animal now native to the Galápagos must have originally dispersed to the island through some means or other. If the organism survived the hazardous journey and was able to survive in the unfamiliar environment, and if there were enough individuals for successful reproduction to occur, a colonizing population would exist. The question that once perplexed biologists was how it was possible for so many venturesome, vagabond species to survive such a long and trying ocean passage to an island when many would surely have perished at the touch of sea water. Exceptional hardships must have been overcome. Nonetheless, close scrutiny of the original flora and fauna of remote islands suggests that they were indeed derived by chance from weedy colonists from the mainland in what has been termed "sweepstakes dispersal". Flotation rafts made of a mat of vegetation or other debris, and even winds and jet streams can be mechanisms of transport for living organisms or seeds to the newly formed islands. Birds displaced from their traditional migratory routes, or seeds and invertebrates hitchhiking on the feathers and feet of aquatic and semi aquatic birds, can also be means of colonization. Of course, species are present in proportion not only to their capacity to disperse, whether actively or passively, but also to their ability to establish themselves after arrival. The need for an appropriate mate in sexually reproducing animals, or a compatible pollinator in out- crossing plants, poses a formidable challenge to long-term establishment. The idea that specific groups of organisms have different hurdle values, which determine the limits of their dispersal, is fundamental to the c concept of disharmony in the living organisms of oceanic islands. Disharmonic floras and faunas are characterized by the absence of conventional groups such as large carnivorous and hooved mammals, amphibians, freshwater fishes and large-seeded forest trees.

Evolution

The Galápagos islands have often been called a "laboratory of evolution". There are few places in the world where it has been possible to find such a variety of species, both plant and animal, which show so many degree of evolutionary changes, in such a restricted area. Once organisms reach oceanic islands they are essentially isolated from other land masses. If the islands are distant enough from a source to make colonization a rare event, then they may be thought of as almost independent biological units. Oceanic islands can have species which, though related to mainland forms, have evolved in ways different from their mainland relatives as a result of their isolation in a different environment. This is a key factor in island evolution. It is not surprising that Charles Darwin was so struck by the life he found on these islands. Formulated by Darwin, Natural Selection is the process by which propagation becomes change, and species diverge one from another. A classic example of adaptive radiation in birds, which has served generations of evolutionary biologists, is Darwin´s finches. A total of 13 species evolved within the Galápagos archipelago from a common ancestor whose founding type and source from the American continent have not yet been identified. A single fourteenth species occurs on Cocos Island off of Costa Rica, about five hundred miles northeast of the Galáapagos. That all the finches are closely related, and presumably evolved from the same progenitor stock, is indicated by a complement of characteristics common to all. The word endemic refers to organisms which are found nowhere else in the world due to the fact that they evolved and remained isolated on a given area and therefore developed unique characteristics. In the Galápagos you will find several species that fall into this classification.

Conservation on the islands

The history of man´s detrimental effects on the islands extends back to the 1600s when buccaneers introduced the first goats and killed tortoise for food. Once settlers came to the islands they brought with them a full range of domestic animals, some of which went wild and started feral populations. Dogs, cats, pigs, goats, rats, the little fire ant, guava plants, and the chinchona (quinine) tree. Introduced plants have spread, particularly in the moist highlands, and compete with native vegetation. Several species are considered to be serious threats to native vegetation. The social and environmental pressures made by the fast growing population of the Galápagos´s inhabited areas cause worry to the national and international communities. Between 1982 and 1990 the population growth rate in Galápagos reached 6% mostly due to immigration from the Ecuadorian mainland. During 1996 step forward in this area was the introduction of an amendment to the Constitution of Ecuador which states that Galápagos will have a special law. Hence, it is possible to restrict indiscriminate immigration, commerce and property rights in Galápagos. Two organizations work together for the conservation of the islands: the Galápagos National Park (GNP), that tries to keep the natural resources of the Islands in the best state of conservation possible and the Charles Darwin Research Station, which conducts and facilitates research in the Galápagos Islands.

Charles Darwin research station

In 1959, the centenary of the publication of Darwin's Origin of Species, the Government of Ecuador and the International Charles Darwin Foundation established, with the support of UNESCO, the Charles Darwin Research Station at Academy Bay 1 ½ km from Puerto Ayora. A visit to the station is a good introduction to the islands as it provides a lot of information. Collections of several rare sub-species of giant tortoise are maintained on the station as breeding nuclei, together with a tortoise-rearing house incorporating incubators and pens for the young. In 1959, the centenary of the publication of Darwin's Origin of Species, the Government of Ecuador and the International Charles Darwin Foundation established, with the support of UNESCO, the Charles Darwin Research Station at Academy Bay 1 ½ km from Puerto Ayora. A visit to the station is a good introduction to the islands as it provides a lot of information. Collections of several rare sub-species of giant tortoise are maintained on the station as breeding nuclei, together with a tortoise-rearing house incorporating incubators and pens for the young.

Geology

Located in one of the most active volcanic regions on earth, the Galápagos are located on the Nazca Plate, close to its junction with the Cocos Plate. As a result of the spreading of the sea floor (the movement of the plates in relation to each other) along the Galápagos Rift and the East Pacific Rise, the islands are moving south and eastward at a rate of more than 7cm/yr., which may not seem fast but would, over a million years or so, amount to 70km of movement! The evidence that the plate on which the islands sit is moving eastward is that the oldest islands are in the eastern part of the archipelago. There is also volcanic activity where the western island are now. In fact, it is on these Western Islands where all the recent volcanic activity has occurred, while the Eastern Islands are the oldest. The "Hot Spot Theory" states that in certain places around the earth, there are more or less stationary areas of intense heat in the mantle. These hot spots cause the crust to melt in certain places and give rise to volcanoes. The Galápagos and Hawaiian Islands have mild volcanic eruptions where volcanic material comes out gently to form large lava flows rather than explosions. The result is that the major Galápagos volcanoes tend to have smooth shield - shaped outlines with rounded tops, rather than cones- like Mt. Fuji in Japan - which were formed by explosive eruptions.

Map of Galapagos Islands

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

|

INFO GALAPAGOS ISLANDS

Introduction

The Galápagos archipelago is famous for its fearless and unique wildlife. Here, you can swim with sea lions, float eye-to-eye with a penguin, stand next to a blue-footed booby feeding its young, watch a giant 200kg tortoise lumbering through a cactus forest, and try to avoid stepping on iguanas scurrying over the lave. The scenery is barren and volcanic and has its own haunting beauty. The Islands lie on the equator, about 1000km west of Ecuador, and consist of 13 major islands and many small ones. Five islands are inhabited. The Galápagos as a whole are one of Ecuador's 21 provinces.

90% of the land surface and all of the ocean out to the national limits was designated a national park in 1959 in order to preserve the original ecology and to control the introduction of new and potentially harmful species. To minimize your impact on the fragile ecology, the park authorities have established certain rules which visitors must abide by and these will be explained by your guide. On land, trails have been established and visitors are expected to keep to the trails. Visitors must not touch, follow or chase the animals and birds nor must they remove any plants or flowers or any other part of the natural history of the islands. Please respect all the rules that you will be told about once there. The survival of the islands depends on you - the visitor.

The islands were discovered accidentally by Tomás de Berlanga, the Bishop of Panama, in 1535. He was on his way to Peru when his ship was swept 800km off course by the currents. In a letter to the King of Spain, the bishop was less than enthusiastic about the islands: "I do not think that there is a place where one might sow a bushel of corn, because most of it is full of very big stones and the earth there is much like dross, worthless, because it has not the power of raising a little grass". Like most of the early arrivals, Bishop Tomás and his crew arrived thirsty and disappointed at the dryness of the place. He did not even give the islands a name.

The islands first appeared on a map in 1574, as "Islands of Galápagos", which has remained in common use ever since. The individual islands, though, have had several names, both Spanish and English. The alter names come from a visit in 1680 by English buccaneers who, with the blessing of the English king, attacked Spanish ships carrying gold and relieved them of their heavy load. The pirates used the Galápagos as a hide-out, in particular a spot north of James Bay on Santiago island, still known as Buccaneers' Cove. The pirates were the first to visit many of the islands and they named them after English Kings and aristocracy, or famous captains of the day. The Spanish also called the islands "enchanted" or "bewitched", owing to the fact that for much of the year they are surrounded by mists giving the impression that they appear and disappear as if by magic. Also, the tides and currents were so confusing that they thought the islands were floating and not real islands.

Arrival and establishment

When the tips of the Galápagos volcanoes first appeared above the sea's surface some three to five million years ago they were devoid of life. The ancestors of every plant and animal species native on the islands must have arrived there from some other part of the world. We will never know exactly how colonization occurred, as such events do not leave records for us, but we may guess about what probably happened.

A thousand kilometers of ocean separate the Galápagos from the mainland. Despite this barrier, a large number of species have made it to the islands. Oceanic volcanic islands such as the Galápagos differ from continental islands in that they never had contact with continental land masses. Any plant or animal now native to the Galápagos must have originally dispersed to the island through some means or other. If the organism survived the hazardous journey and was able to survive in the unfamiliar environment, and if there were enough individuals for successful reproduction to occur, a colonizing population would exist. The question that once perplexed biologists was how it was possible for so many venturesome, vagabond species to survive such a long and tiring ocean passage to an island when many would surely have perished at the touch of sea water. Exceptional hardships must have been overcome. Nonetheless, close scrutiny of the original flora and fauna of remote islands suggests that they were indeed derived by chance from weedy colonists from the mainland in what has been termed "sweepstakes dispersal". Flotation rafts made of a mat of vegetation or other debris, and even winds and jet streams can be mechanisms of transport for living organisms or seeds to the newly formed islands. Birds displaced from their traditional migratory routes, or seeds and invertebrates hitchhiking on the feathers and feet of aquatic and semi aquatic birds, can also be means of colonization. Of course, species are present in proportion not only to their capacity to disperse, whether actively or passively, but also to their ability to establish themselves after arrival. The need for an appropriate mate in sexually reproducing animals, or a compatible pollinator in out-crossing plants, poses a formidable challenge to long-term establishment. The idea that specific groups of organisms have different hurdle values, which determine the limits of their dispersal, is fundamental to the concept of disharmony in the living organisms of oceanic islands. Disharmonic floras and faunas are characterized by the absence of conventional groups such as large carnivorous and hoofed mammals, amphibians, freshwater fishes and large-seeded forest trees.

Evolution The Galápagos islands have often been called a "laboratory of evolution". There are few places in the world where it has been possible to find such a variety of species, both plant and animal, which show so many degree of evolutionary changes, in such a restricted area. Once organisms reach oceanic islands they are essentially isolated from other land masses. If the islands are distant enough from a source to make colonization a rare event, then they may be thought of as almost independent biological units. Oceanic islands can have species which, though related to mainland forms, have evolved in ways different from their mainland relatives as a result of their isolation in a different environment. This is a key factor in island evolution. It is not surprising that Charles Darwin was so struck by the life he found on these islands. Formulated by Darwin, Natural Selection is the process by which propagation becomes change, and species diverge one from another. A classic example of adaptive radiation in birds, which has served generations of evolutionary biologists, are Darwin finches. A total of 13 species evolved within the Galápagos archipelago from a common ancestor whose founding type and source from the American continent have not yet been identified. A single fourteenth species occurs on Cocos Island off of Costa Rica, about five hundred miles northeast of the Galápagos. That all the finches are closely related, and presumably evolved from the same progenitor stock, is indicated by a complement of characteristics common to all. The word endemic refers to organisms which are found nowhere else in the world due to the fact that they evolved and remained isolated on a given area and therefore developed unique characteristics. In the Galápagos you will find several species that fall into this classification. If the islands are distant enough from a source to make colonization a rare event, then they may be thought of as almost independent biological units. Oceanic islands can have species which, though related to mainland forms, have evolved in ways different from their mainland relatives as a result of their isolation in a different environment. This is a key factor in island evolution. It is not surprising that Charles Darwin was so struck by the life he found on these islands. Formulated by Darwin, Natural Selection is the process by which propagation becomes change, and species diverge one from another. A classic example of adaptive radiation in birds, which has served generations of evolutionary biologists, are Darwin finches. A total of 13 species evolved within the Galápagos archipelago from a common ancestor whose founding type and source from the American continent have not yet been identified. A single fourteenth species occurs on Cocos Island off of Costa Rica, about five hundred miles northeast of the Galápagos. That all the finches are closely related, and presumably evolved from the same progenitor stock, is indicated by a complement of characteristics common to all. The word endemic refers to organisms which are found nowhere else in the world due to the fact that they evolved and remained isolated on a given area and therefore developed unique characteristics. In the Galápagos you will find several species that fall into this classification.

Conservation on the islands

The history of man's detrimental effects on the islands extends back to the 1600s when buccaneers introduced the first goats and killed tortoises for food. Once settlers came to the islands they brought with them a full range of domestic animals, some of which went wild and started feral populations. Dogs, cats, pigs, goats, rats, the little fire ant, guava plants, and the chinchona (quinine) tree. Introduced plants have spread, particularly in the moist highlands, and compete with native vegetation. Several species are considered to be serious threats to native vegetation. The social and environmental pressures made by the fast growing population of the Galapagos' inhabited areas cause worry to the national and international communities. Between 1982 and 1990 the population growth rate in Galápagos reached 6% mostly due to immigration from the Ecuadorian mainland. During 1996 step forward in this area was the introduction of an amendment to the Constitution of Ecuador which states that Galápagos will have a special law. Hence, it is possible to restrict indiscriminate immigration, commerce and property rights in Galápagos. Two organizations work together for the conservation of the islands: the Galápagos National Park (GNP), that tries to keep the natural resources of the Islands in the best state of conservation possible and the Charles Darwin Research Station, which conducts and facilitates research in the Galápagos Islands.

Charles Darwin Research Station In 1959, the centenary of the publication of Darwin's Origin of Species, the Government of Ecuador and the International Charles Darwin Foundation established, with the support of UNESCO, the Charles Darwin Research Station at Academy Bay 1 ½ km from Puerto Ayora. A visit to the station is a good introduction to the islands as it provides a lot of information. Collections of several rare sub-species of giant tortoise are maintained on the station as breeding nuclei, together with a tortoise-rearing house incorporating incubators and pens for the young.

Geology

Located in one of the most active volcanic regions on earth, the Galápagos are located on the Nazca Plate, close to its junction with the Cocos Plate. As a result of the spreading of the sea floor (the movement of the plates in relation to each other) along the Galápagos Rift and the East Pacific Rise, the islands are moving south and eastward at a rate of more than 7cm/yr., which may not seem fast but would, over a million years or so, amount to 70km of movement! The evidence that the plate on which the islands sit is moving eastward is that the oldest islands are in the eastern part of the archipelago. There is also volcanic activity where the western island are now. In fact, it is on these western islands where all the recent volcanic activity has occurred, while the eastern islands are the oldest. The "Hot Spot Theory" states that in certain places around the earth, there are more or less stationary areas of intense heat in the mantle. These hot spots cause the crust to melt in certain places and give rise to volcanoes. The Galápagos and Hawaiian Islands have mild volcanic eruptions where volcanic material comes out gently to form large lava flows rather than explosions. The result is that the major Galápagos volcanoes tend to have smooth shield - shaped outlines with rounded tops, rather than cones - like Mt. Fuji in Japan - which were formed by explosive eruptions.

The Galápagos Islands

Santa Cruz With a surface of 986 km², Santa Cruz is the second largest of the Archipelago. Colonized since the 1920´s, Puerto Ayora, the populated part of the Island, is the most important harbor of the Archipelago. Here you can find many hotels and restaurants. With altitudes reaching 864m this island comprises all plant zones, ranging from coast to pampas. The headquarters of the Galápagos National Park and the Charles Darwin Station are also located in Santa Cruz. North of Santa Cruz, separated by a narrow strait, is Isla Baltra, with the islands' major airport. A public bus and a ferry connect the Baltra airport with Puerto Ayora.

Attractions:

- Galapagos Giant Tortoise

- Pacific Green Turtle

- Land Iguana

- Galapagos Sea Lion

- Red-Billed Tropic Bird

- Swallow-Tailed Gull

- Typical humid zone vegetation

- Miconia bushes- Scalesia trees

- pampa (fern-sedge zone)

- extinct volcanic cones

Charles Darwin Research Station

Although the great majority of Galapagos visitors come here to observe and appreciate the area's natural wonders, it is also interesting to learn how the protection and conservation of the islands is carried out. By visiting the facilities of the Darwin Station and National Park, it is hoped that the visitor will begin to realize that not only scientists, but also professional administrators and Park wardens must exert an enormous, costly effort to maintain the islands ecosystems, and some of the endangered species which comprise them, in their natural state so that people may enjoy them for many years to come.

Attractions:

- Adult Galapagos tortoises in captivity

- Center for raising young tortoises

- Van Straelen Exhibit Hall

- National Park Information Center

Isla Isabela (Albemarle) Isabela was formed by five independent volcanoes that came together and is the largest (4588 km²) of the islands, and has the highest elevation as well (Wolf, 1677m). Inhabited on its southern tip, and once a penal colony, Isabela is also characterized by its natural diversity. The northwest coast of Isabela is a sanctuary for whales. Ask your naturalist guide about the whale watching program. Tagus Cove was the favorite site of early pirates and whalers, and part of a historical tradition (now discouraged) of graffiti, with its cliffs filled with the names of the ships that visited (including some famous vessels). A moderate hike up to Darwin Lake in order to admire the vegetation and the landscape, is worthwhile doing. Urvina Bay: This area, located on the western coast of Isabela Island at the foot of Alcedo Volcano, was uplifted from the sea in 1954. The site is relatively flat, distinguished by corals and other marine formations which were lifted out of the sea by the uplift. Flightless cormorants and pelicans nest along the coast during their nesting seasons.

Attractions:

-

- Land Iguana- Galápagos Penguin

- Galápagos Fur Seal

- Galápagos Sea Lion

- Galápagos Giant Tortoise

- Pacific Green Turtle

- Flightless Cormorant

- Greater Flamingo

- Vermillion Flycatcher

Isla Santiago (San Salvador)

With a surface area of 585km², Santiago is the fourth larges island. Its main volcano rises to a height of 907m. All vegetation zones, from coastal to humid, are represented. However, the vegetation of Santiago is altered due to the presence of feral goats. Santiago is one of the best islands to see the Galápagos fur seal and the hawk.

Attractions:

- Galapagos Penguin

Isla Floreana (Santa Maria) An island with a gentle landscape dominated by parasitic cones. If a central volcano ever existed, it has eroded, long ago. This island, 640m high, was the first inhabited island of the Archipelago. Still scarcely and endowed with a bizarre collection of stories, Floreana, beholds beautiful visitor's sites, one of the few, where flamingos can be found. Further the island is home to the Post Office Barrel (wooden barrel placed there in the 18th century by the crew of a whaling ship) and the Lava Cave.

Attractions:

- Red-Billed Tropic Bird

- Galapagos Sea Lion

- Greater Flamingo

Isla Fernandina (Narborough)

Fernandina is located at the west end of the archipelago. The colossal shield of Fernandina Volcano, reaches 1,494 m and is still very active. The island has a surface area of 643km² and is one of the most pristine areas of the Galápagos. Its vegetation, typical of the arid zone, is concentrated in "kipukas" (small areas left untouched by recent lava). Fernandina is an impressive island, with a broad variety of wildlife and volcanic features. Punta Espinosa, at the northeast coast of the island is the only area open to visitors and is formed by lava and sand, and harbors one of the largest communities of marine iguanas, as well as sea lions and flightless cormorants.

Attractions:

- Marine Iguana

- Flightless Cormorant

- Galapagos Sea Lion

Isla Genovesa (Tower) The only of the northern islands of the Archipelago open to visitors. This 14 km² island is the tip of a submerged shield volcano, that rises 76m above the sea level. Its central crater is filled with salt water. Ocean erosion created the Darwin-Bay on the southern slope. Genovesa is a very dry island, with a characteristic vegetation. Because of its isolated position with respect to the rest of the Archipelago, Genovesa lack reptiles, except for the marine iguanas. However, it is a paradise for sea birds, including large colonies of the red-footed boobies and great frigate birds.

Attractions:

- Masked Booby

- Red-Footed Booby

- Frigate Birds

- Red-Billed Tropic Bird

- Swallow-Tailed Gull

- Marine Iguana

- Galapagos Fur Seal

Isla Santa Fe (Barrington)

This 24km² island is the result of an uplifting that rose the sea floor 259m above the sea level. The vegetation of the island is characterized by the presence of the larges species of the giant opuntia cactus. Two animal species highlight this island: The Santa Fe land iguana and the Galápagos rice rat.

Attractions:

- Land Iguana

- Galapagos Sea Lion

Isla San Cristóbal (Chatham) The southwestern half of this 558km² island is inhabited, and is formed by an extinct volcano. This part is characterized by lush vegetation and abundant water (including fresh water lakes). The highest point reaches 730m. The other half of the island, the northeastern part, contrasts dramatically, with flat, dry and harsh environments. San Cristóbal was colonized during the 1860s, when Puerto Baquerizo Moreno was founded. In 1888 Manuel Cobos founded El Progreso, a sugar cane plantation. In 1904, Cobos was murdered by one of his workers but his descendants still live on the island.

Attractions:

- Blue-Footed Booby

- Frigate Birds

- Galapagos Sea Lion

- Galapagos Giant Tortoise

Isla Española (Hood)

A relatively flat island (206m in altitude). Its rocks are among the oldest in the Archipelago. Some geologists describe the 60km² island as the remains of an eroded archaic volcano. The vegetation corresponds to arid and transition zones. The west point of Española is one of the most spectacular sites of the Galápagos, with diverse and interesting wildlife.

Attractions:

- Waved Albatross

- Red-Billed Tropic Bird

- Swallow-Tailed Gull

- Masked Booby

- Blue-Footed Booby

- Galápagos Sea Lion

- Marine Iguana

How to get there Flying to the Galápagos is recommended. Tame Airline and AeroGal have daily flights on the routes Quito - Guayaquil - Galápagos and vice versa. The airplane lands on the Baltra Island airport, separated from the Santa Cruz Island by the Canal of Itabaca. Flights will be arranged by the school. This way we can assure you a enjoyable journey without worrying about reservations and reconfirmations. A school staff member will meet you at the airport in Baltra and take you to Puerto Ayora. Every visitor has to pay a National Park Tax of US$ 110.--, payable only in US$ cash. It is paid on arrival, or at Quito or Guayaquil airports on request.

Climate

Marine currents and weather despite their tropical location, the islands are surrounded by relatively cold waters brought northwards by the Humboldt Current. The Galápagos has two main seasons, each of which has an effect on the flora and fauna: the warm and wet season from January to June and the cold and dry (garúa) season, from July to December. During the garúa season, cooler waters from the Humboldt Current are driven to the Galápagos by the southeast trade winds, with an average sea temperature of 22ºC (71ºF).

As a result, there is warm tropical air passing over cool water. The moisture evaporating from the sea is concentrated in an inversion layer (300 to 600 m above sea level) and the higher parts of the islands, which intercept this layer, receive precipitation in the form of garúa (mist rain). While lowland areas remain dry though cool. During the warm season the southeast trade winds diminish in strength and warmer waters from the Panama Basin flow through the islands. The average sea temperature rises to 25º C (77º F). Warmer waters cause the cool season inversion layer to break up, and Galápagos experience a more typical tropical climate with blue skies and occasionally heavy showers. In some years, the flow of warm water is much greater than normal, and an "El Niño" year results. Surface water temperatures are higher and rainfall can increase greatly. Life on land blossoms but seabirds and sea life, which depend on the more productive, cooler waters, may experience dramatic breeding failures. Daytime clothing should be lightweight. At night, however, particularly at sea and at higher altitudes, temperatures fall below 15°C and warm clothing is required. Boots and shoes soon wear out on the lava terrain. The sea is cold July-Oct; underwater visibility is best Jan-March. Sept is the low point in the meteorological year.

What to bring Take note of the weather conditions as discussed above relative to the time of year you will be traveling. In any case, dress is casual and informal and you should bring shorts; long trousers, long and short sleeve lightweight shirts; a windbreaker and light sweater; walking shoes or tennis shoes and bathing suit. Also remember to bring your passport; a lockable suitcase or backpack; sunglasses with strap; wide brimmed hat; sunscreen/ suntan lotion/ chap stick; camera (with UV and/or polarizing filter); film (64 and 100 ASA work best) - the use of one 36 exposure film per day is not uncommon; a day pack; seasickness medication; a 1litre water bottle and snorkeling equipment if you have it.

Rules of the Galápagos National Park

On the islands, groups of no more than 15 visitors are led by a naturalist certified by the Galápagos National Park Service. With this policy it is intended to reduce the impact on the fragile ecosystems while providing a sense of solitude and privacy on the Islands. Don't take anything from the islands, but photographs, and leave only your footprints.

- Please do not disturb or remove any native plant, rock, or animal.

- Please be careful not to transport any live material to the islands or from island to island. Each one has its unique fauna and flora and introductions can quickly destroy their balance.

- Please do not touch or handle animals. Even the fearless animals of the Galápagos require a certain distance, and do not like to be encroached upon. Please respect this distance as attempting to touch them will disturb them.

- Please do not feed the animals. This can be dangerous to you and it will also affect the social structure and natural behavior of the animals.

- Please do not startle of chase any animal from its resting or nesting spot.

- Please stay on the marked trails. Many people visit the islands and it is important that people do not damage vegetation or cause erosion.

- Please do not leave, or throw any litter over board.

- Please do not buy any souvenirs made from native Galápagos precuts, (except for wood) as this encourages the exploitation of these resources. Especially do not buy sea lion teeth, black coral, or tortoise/turtle shell products.

- Do not smoke on the islands.

- Do not hesitate to show your conservationist attitude.

|

|

If the islands are distant enough from a source to make colonization a rare event, then they may be thought of as almost independent biological units. Oceanic islands can have species which, though related to mainland forms, have evolved in ways different from their mainland relatives as a result of their isolation in a different environment. This is a key factor in island evolution. It is not surprising that Charles Darwin was so struck by the life he found on these islands. Formulated by Darwin, Natural Selection is the process by which propagation becomes change, and species diverge one from another. A classic example of adaptive radiation in birds, which has served generations of evolutionary biologists, are Darwin finches. A total of 13 species evolved within the Galápagos archipelago from a common ancestor whose founding type and source from the American continent have not yet been identified. A single fourteenth species occurs on Cocos Island off of Costa Rica, about five hundred miles northeast of the Galápagos. That all the finches are closely related, and presumably evolved from the same progenitor stock, is indicated by a complement of characteristics common to all. The word endemic refers to organisms which are found nowhere else in the world due to the fact that they evolved and remained isolated on a given area and therefore developed unique characteristics. In the Galápagos you will find several species that fall into this classification.

If the islands are distant enough from a source to make colonization a rare event, then they may be thought of as almost independent biological units. Oceanic islands can have species which, though related to mainland forms, have evolved in ways different from their mainland relatives as a result of their isolation in a different environment. This is a key factor in island evolution. It is not surprising that Charles Darwin was so struck by the life he found on these islands. Formulated by Darwin, Natural Selection is the process by which propagation becomes change, and species diverge one from another. A classic example of adaptive radiation in birds, which has served generations of evolutionary biologists, are Darwin finches. A total of 13 species evolved within the Galápagos archipelago from a common ancestor whose founding type and source from the American continent have not yet been identified. A single fourteenth species occurs on Cocos Island off of Costa Rica, about five hundred miles northeast of the Galápagos. That all the finches are closely related, and presumably evolved from the same progenitor stock, is indicated by a complement of characteristics common to all. The word endemic refers to organisms which are found nowhere else in the world due to the fact that they evolved and remained isolated on a given area and therefore developed unique characteristics. In the Galápagos you will find several species that fall into this classification.

The Spanish also called the islands "enchanted" or "bewitched", owing to the fact that for much of the year they are surrounded by mists giving the impression that they appear and disappear as if by magic. Also, the tides and currents were so confusing that they thought the islands were floating and not real islands.

The Spanish also called the islands "enchanted" or "bewitched", owing to the fact that for much of the year they are surrounded by mists giving the impression that they appear and disappear as if by magic. Also, the tides and currents were so confusing that they thought the islands were floating and not real islands. In 1959, the centenary of the publication of Darwin's Origin of Species, the Government of Ecuador and the International Charles Darwin Foundation established, with the support of UNESCO, the Charles Darwin Research Station at Academy Bay 1 ½ km from Puerto Ayora. A visit to the station is a good introduction to the islands as it provides a lot of information. Collections of several rare sub-species of giant tortoise are maintained on the station as breeding nuclei, together with a tortoise-rearing house incorporating incubators and pens for the young.

In 1959, the centenary of the publication of Darwin's Origin of Species, the Government of Ecuador and the International Charles Darwin Foundation established, with the support of UNESCO, the Charles Darwin Research Station at Academy Bay 1 ½ km from Puerto Ayora. A visit to the station is a good introduction to the islands as it provides a lot of information. Collections of several rare sub-species of giant tortoise are maintained on the station as breeding nuclei, together with a tortoise-rearing house incorporating incubators and pens for the young.